Often when I write to poets asking for permission to use their poems they’ll ask, ‘ how did you find me?’ And 90% of the time I can’t remember. I spend a lot of my time flicking in and out of various poetry web sites and often one poem will lead me to another and then on to another poet and so it goes on…….. When I first read Mick’s poem, (and no I can’t recall where), I knew I wanted it for the cards. It took me several months to track Mick down and after explaining who I was and why I’d like a loan of his poem the reply came back…

I’d be honoured if you would include my poem on your poetry card. It was written specifically to support a good friend going through a difficult time and if it can do the same for others so much the better.

We communicated several times and Mick mentioned that he used to visit New Zealand during his business career. Unfortunately I never got to explore much – mainly office and factory visits in and around Auckland, punctuated by the odd game of squash with my colleagues. Beautiful country, though, and lovely people.

So when I contacted Mick in early February asking him if his poem could be included in the selection I was offering to the artists he was as enthusiastic as ever.

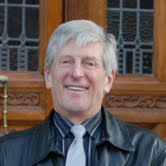

Introducing Mick Stringer:

This is a relatively recent picture of myself in front of my old school in Bradford, with which I still have close links.

Ahhh, my favourite place? Well it has to be Ilkley Moor. I was born in Yorkshire (although I now live in the South of England) and this is the emblematic place for all Yorkshire folk.

Mick Stringer

A life

(Sorry – totally pretentious but utterly irresistible!)

According to my mother I was born during a thunderstorm in July, 1944, but allowing for her gift of dramatic exaggeration it is just as likely that the event was accompanied by an unremarkable passing shower of light rain. The place was Bradford in West Yorkshire, once the capital of the world’s wool trade, a city of blackened millstone grit and a stubborn character to go with it.

At the age of eleven I won a scholarship to the Grammar School. I never got along with the discipline and petty regulations and in those days when canes still ruled, I collected the marks to prove it. But I had some great teachers and absorbed a love of languages and literature that has lasted a lifetime.

Seventeen years old, and with all the arrogance of youth, I made my way to Rotterdam and signed on as a galley boy on a South America bound cargo ship. It was an eventful experience, including a miraculous survival when in a moment of over exuberance I leapt on the back of a Brazilian policeman and removed his gun from its holster. Fortunately my shipmates were nearby and I believe a certain amount of money changed hands.

Possibly this incident persuaded me that a mariner’s life was not for me, and back in the UK I drifted from job to job, with occasional breaks to travel around Europe, until I ended up as a cost and production clerk in a secondary aluminium refinery. I loved the factory life, the boiling metal, the heavy machines, the sweat. At the same time I joined a local theatre group, treading the boards in productions of Othello and King Lear and in my spare time teaching the new-fangled “method acting” to enthusiastic youngsters all of three or four years younger than me.

Eventually, I decided that to get on in life I needed to resume my education. I went to night school, obtained the necessary entrance qualifications, and at the grand old age of twenty-three won a place to read Psychology and English at Keele University. My then girlfriend, Kate, was already studying at a nearby teachers’ training college, and we have been together ever since.

After four years in academia I was hungry to return to factory life. I got a position as a Management Trainee at a cooker factory in Birmingham, studied for my accounting exams by correspondence course, and won rapid promotion. Still in my early thirties I was appointed to the board of a Leeds-based company manufacturing heavy-duty hydraulic equipment for the global market. I travelled extensively, indulging my love of languages, learning about the shades and nuances in cultures we think we understand but really don’t.

It would be tedious to recount the rest of my business career. It ended long after I had left the North behind and had become the proud father of two fabulous daughters, now mothers themselves. I phased myself out, part-time interim management, a bit of consulting here and there, a return to creative writing, and, finally, signing on to do a part-time Classics degree at Reading University. I’m still there. I obtained my BA, then my MA and am now approaching the half-way stage of my PhD. My thesis, “Words, Numbers and Economic Rationalism”, uses the work of Roman writers on agriculture to show how language and accounting systems shape our views of what is economically rational, providing, I like to think, some lessons for today’s bankers and financial managers. In a way it is a culmination of my career, pulling together the threads of behavioural science, language, business and the classical world that have run through my life.

I have been writing poems and stories since my youth. Several have found a home in various “small press” publications, my three novels, alas, remain unpublished. I love the Waiting Room idea. The thought that a few of my lines can help someone through moments, minutes, even hours of anxious waiting is a humbling one, but if they really do help, that must be worth more than any royalty cheque, or their presence in some glossy hard backed coffee table volume that is rarely, if ever, opened.

My poetic biography is more colourful:

The Journey

Open the hatches and unlash the wheel

the storm is nearly blown

and our hero has been thrown

from the deep and dark blue sea

flesh all sanded throat washed dry

upon that beach of rainbow sands

where one rare and southern holiday

I spooned my childish colours

in a crystal tube of hope

mosaics that bumping homewards

merged to dull homogenous brown

Home where grey grass tufted

flecked with white by withering winds

dying as if a locust perched

and gnawed at every blade

where thick black lines of chimneys

crossed sunset’s copper sky

and in pubs and chapels singers

sang of one to come in flames

home where I learned out on the moors

that neither god nor lover lived

up in that copper sky

Black walls crossed the dying fields

beneath that northern heaven

stone everywhere dark as the sea

under a starless night

stone steps squeezing up alleys steep

stone snickets licked by stuttering lights

stone shadows scuttling like rusty leaves

along stone streets into stone corners heaped

I slipped between the sooty bulks

of church and school and mills

in that hard land of stone

Love promised that tomorrow

I would drink bright-coloured dreams

shining as the morning sun

that slants through painted windows

in the church atop the hill

love brought rain too

and inked the quiet waters

where I sat with her in stillness

by a stream that cut the moor

and once there was a bitter frost

that pinched love’s leaves all black

This is the sea we walked by once

it still goes on still stirs

the popping seaweed fills the pools

with tiny creatures waving at the shore

still rolls the tides of memory

as the world’s flat engine pinks

here is the wood where the horses blew

the cobbles that rattled the crates

the pond where the drifting bobbing boats

whispered their hopes to the water

these I will never forget

Nor will I ever forget

how the night’s lights glowed when I drove away

and the fair spun on without me

I have come far from those grey-grassed fields

and those shattered chequered walls

I have come far from the copper sky

and the smoking chimney stacks

thrown by time back on the beach

to sort my sands anew

to recreate a rainbow life

from scenes of long ago

I emailed Mick requesting some photos, and this morning four were sitting in my ‘in box’ – perfect companions to ‘The Journey.’

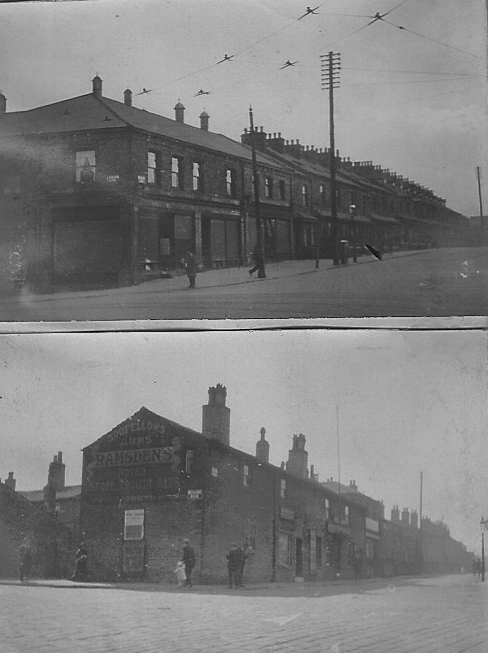

That hard land of stone. My grandfather, who died before I was born, was something of a local historian and I have his notes on the area in which I grew up – Lidget Green in Bradford. These are his pictures of some of the buildings around the Green. A total misnomer by the 1930s when I guess the photos were taken – not a trace of vegetation to be seen.

This is the sea we walked by … In 1999 I completed the Coast to Coast walk, from the west to the east of England. This is me at the end of the journey – standing on the beach at Robin Hood’s Bay in North Yorkshire.

Here is the wood where the horses blew. This was taken a mile or so from where I now live in Maidenhead. Such winters are rare down here in the South but they were the norm when I was growing up in Yorkshire.

To sort my sands anew … This shows my daughters when they were girls playing among the rainbow sands at Alum Bay on the Isle of Wight. It was here that, as a boy, I too collected sands of many colours. Nowadays the place is fully commercialised and I believe you collect your sands from rows of boxes instead of climbing the crumbling cliffs. Shame

And three more poems from Mick

View from a Tower

Here is the limit of our world.

The blood of our eternal city

Flows this far and nourishes.

Beyond is wind and water,

Barbarous land that never bore the vine.

Standing on the eighth mile tower,

I, Marcus Quintus, Legion Six – Victrix-

Span the cusp of time,

Stretch eyes and mind into the fading far,

Seeking the stone-clad firmness of the square.

The certain road cuts to the midday sun:

Eboracum, then Lindum, through Londinium;

Beyond, our galleys ply the leaden sea

And double lines of legionaries

March to the Forum and the Capitol.

I look back to the golden glow of dawn

When our proud eagles rose

And, with our sturdy soldiery, spread our peace,

Our modest virtues, honour, love of home.

With these we conquered.

For these we spilled our blood.

In the name of these we died.

Then I peer forward

Through damp mists to a cold sea.

The view dissolves in drops

That fall and cling to clumps of reedy grass,

Bending with drizzled beads of dull uncertainty.

I see strange tribes

With mad, confusing symbols on their shields,

Beating before them fire and smoke,

Leaving behind a boiling wilderness.

I cannot see their gods.

They must be terrifying.

Standing on the eighth mile tower,

My plated armour weighs,

The leather chafes, my sodden cloak hangs limp.

But here, I know, in space and time

Exactly where I am.

I am glad of that.

View from a Tower was recently published in The University of Reading Creative Arts Anthology : “One Moment’s Clouds” (ISBN 978-0-7049-1532-9).

Frames

Right-angled corners

windows, edges, frames

condense the world outside

to manageable fragments

disconnected

from the wider view.

A TV aerial defines

a rectangle of sky

thickens the blue

renders possessable

a sector of infinity

where a plane –

a silver dot dragging a vapour trail –

scratches the sky

like a razor cuts the skin

cleanly

quickly closing

gone.

There was a time before me

another when I was but did not know

among a billion mirrors

reflecting eternity

from three slim slivers

I smile out

shake my rattle

wed

collect my watch.

Beyond me there will be

a sweep of street

blocked out by shrubs

some stretch of sky above the house

where clouds dissolve

or build to shapes

fantastic

and unknown.

There is forever

in that unframed vastness

when my edges are unpicked

and laid aside.

You’ll find a bridge

The river

gorged with cold spring rain

hollowed our ears with its rushing

dragged bankside grass

into the stream

flowing like hair

on a drowned Ophelia.

Failing to tent the race

the stepping stones

thrust into the flood

smooth backs

of glass-capped purity.

We stood uncertain

blocked

by all this sea-bound urgency.

A throbbing tractor

thumped the river’s roar

rattled a cart on a rutted track

then stopped and gently idled

while a voice

as firm but moss-soft as a limestone wall

burred

“You’ll find a bridge up there.”

In the cart

snout flat against the deck

a sheep

a mound of grey-curled lanolin

nuzzled her lamb

a sopping pulse

with twigs of untried legs

birth-streaked with blood.

“She’s cold. Don’t want to feed.”

“Will she be right?”

“Aye. Needs a bit of warmth.”

His crinkled face was weathered

brown and invisible

against the brackened moors

but the eyes

washed clear by life and death

spoke care and comfort to us.

“You’ll find a bridge. Can’t miss it.”

Then the perfect whole

of farmer, ewe and lamb

clattered off towards some straw strewn barn.

We found our bridge.

I wonder, though,

did they?

“You’ll find a bridge” is, of course, located in Yorkshire. By the way, if you’re interested in my academic (as against literary) interests there’s a bit of stuff on the Academia website: http://reading.academia.edu/MickStringer

Pingback: Mick Stringer Poeticus | News from the Department of Classics at Reading