Kate is a novelist and short story writer based in Aro Valley, Wellington. After completing the MA in Creative Writing in 2000 at Victoria University, her novel Breakwater (2001) was published by Victoria University Press. She has published in Landfall and Sport, and been anthologised in The Penguin Book of Contemporary New Zealand Short Stories (2009) and the Anthology of New Zealand Literature (2012). Kate held the Robert Burns Fellowship at Otago University in 2004. She has taught short fiction workshops at Victoria University for the past three years and continues to supervise for the MA programme while working on her PhD.

Kate is a novelist and short story writer based in Aro Valley, Wellington. After completing the MA in Creative Writing in 2000 at Victoria University, her novel Breakwater (2001) was published by Victoria University Press. She has published in Landfall and Sport, and been anthologised in The Penguin Book of Contemporary New Zealand Short Stories (2009) and the Anthology of New Zealand Literature (2012). Kate held the Robert Burns Fellowship at Otago University in 2004. She has taught short fiction workshops at Victoria University for the past three years and continues to supervise for the MA programme while working on her PhD.

Kate says

When I was in my early twenties, I did a fair amount of sitting in pyjamas half the day attempting to write poetry and the beginnings of stories. Somewhere along the line fiction became the “thing that I do” and poetry an occasional game. So I feel pleased, but also unnerved when one of these occasional poems makes it out into the world. I start wanting to make disclaimers. I’ve met enough “real” poets now to know that I’m not one.

But it’s nice somehow to think about that girl in pyjamas. I had long hours back then for reading over and over again James K Baxter, Hone Tuwhare, Jenny Bornholt, Lauris Edmond, Alistair Te Ariki Campbell.

My first year textbook, ‘Seven Centuries of Poetry in English’ has survived dozens of bookshelf culls in the years since, stained with raspberry jam from eating donuts over it on the train on my way to my waitressing job in Johnsonville. The voices rise clear and loud off the page as I flick through it. Ted Hughes, ‘A cool small evening shrunk to a dog bark and the clank of a bucket- ’ (Full Moon and Little Frieda); the blessing at the end of Auden’s Lullaby:

Let the winds of dawn that blow

Softly round your dreaming head

Such a day of welcome show

Eye and knocking heart may bless,

Find our mortal world enough;

Noons of dryness find you fed

By the involuntary powers,

Nights of insult let you pass

Watched by every human love.

The next year I took Bill Manhire’s course in Modern Poetry and was introduced to Adrienne Rich, Eavan Boland, and Seamus Heaney. Each of these three opened up windows in my head: Rich’s passionate, politically engaged poems (‘The decision to feed the world/is the real decision’); Boland on motherhood, (‘A silt of milk/the last suck./And now your eyes are open,/Birth-coloured and offended.’) and Heaney’s poems where land and language meld into one another: ‘The tawny guttural water/spells itself: Moyola/is its own score and consort’.

These poets shaped the way I felt and understood as I was first coming into my adult life. The words crept inside, laid themselves along the lines of bone, wove into my sinews and synapses. No disrespect to the kids today, but I’m glad there was no Google, Facebook and Twitter when I was twenty-one, because I’m pretty sure for me the cyberbabble would have eaten up that solitary reading.

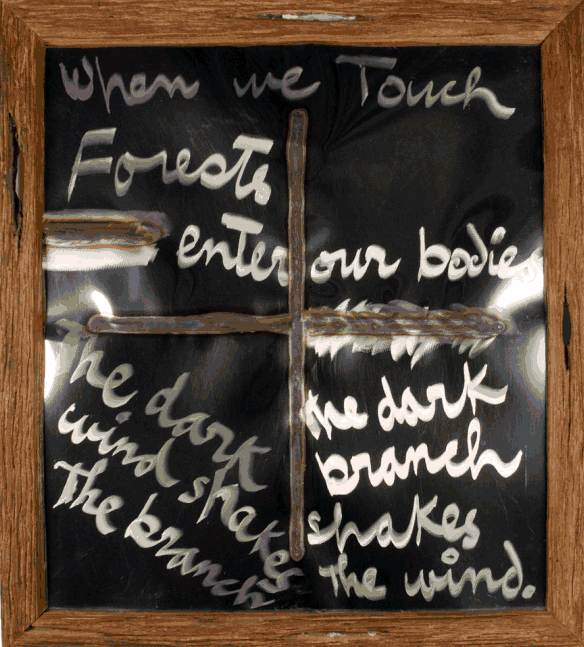

Somewhere in the late 1990s there was an exhibition of Hotere’s work at the Wellington Art Gallery. There were plenty of paintings, but the ones I spent longest with were the Hotere/Manhire collaborations. Long before Bill taught me in a classroom, there were these lyrics: yearning, playful, mysterious, magical. My favourite (I could even tell you exactly where it hung in the gallery) was Hotere’s painting of this poem, a poem which is has now turned into a song on the Buddhist Rain album.

The Voyage

(Bill Manhire)

1

All night water laps

the hedges. I hold you in the middle

of the air.

2

Don’t sleep

all night. It is pitch

black, but since

there is a vista, let

your throat be

the lantern.

3

Since there is

a window, let us

open it.

4.

Let us dress

for a voyage, Let me

go out, with

your voice, to call for you.

My poem for the Bellamys exhibition was written perhaps eight years ago, when my grandparents were both still well and living in their home in Lower Hutt. The poem looks back to being a child in that house, but writing it was really a way of glancing ahead to the time when Molly and Jack would die, and their house would be sold. All that has happened now. One of the reasons I’m pleased to have written this is because I think of Molly every time I bake with my four and two-year-old daughters.

Grandmother

When I was five

you taught me how to separate an egg.

I watched you tap it on the rim

of the bowl,

press your thumbs to the spot

and crack it clean in two.

You let me take the speckled shell

in my own hands

and rock the yolk back and forth,

quivering

as it slid from one half to the other,

a tiny yellow sun.

We put the splintered pieces

in the brown bin

for the compost

and the empty carton

in the red bin

for the incinerator.

In the garden,

the light went out of the golden elm.

We stood at the window.

The moon was a white cup.

The birds had gone to their nests, you said

and tomorrow would be a good day.

I spread my fingers on the dark glass.

Our cake, you said, would rise.

Kate Duignan